Identifying & Classifying Diabetes

As Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) and health care professionals (HCPs), the types of diabetes we are most

familiar with are type 2 diabetes (T2D), type 1 diabetes (T1D), and gestational

diabetes (GDM). We may be least acquainted with other, less common types of

diabetes, including ketosis-prone diabetes (KTD), monogenic diabetes (mature-onset

diabetes of youth [MODY]), and latent-autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA). Other

types are complications of other disorders (eg, cystic fibrosis, post-organ transplant,

secondary due to certain medications, trauma, and cancer). The challenge is appropriately

classifying the type of diabetes someone has and initiating the appropriate

treatment as soon as possible.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently estimates that 90%

to 95% of the people with diabetes in the United States have a diagnosis of

T2D and 5% to 10% have a diagnosis of T1D. There is emerging data that suggests

T1D is more common, and that many adults are often misdiagnosed as

having T2D.

Understanding T1D will assist DCESs and HCPs in our ability to identify it –

or at least to have a higher degree of suspicion for those at risk when it

exists in earlier, pre-clinical stages. Type 1 diabetes is a progressive,

autoimmune disease characterized by the loss of the insulin-secretory

function of the pancreatic beta-cell over time and in 3 distinct stages.

The staging of T1D will be elaborated on in Section 2.

Incidence of T1D

A review of the epidemiological data helps us understand who is developing T1D and at what age.

As many as 64,000 Americans are diagnosed with T1D each year. Type 1 diabetes is formerly known as ‘juvenile-onset” diabetes. It remains one of the most common chronic childhood diseases. Its onset peaks between age 10 and 14 years. Yet, 58% of new cases are diagnosed in the adult population, with a steady rise beginning around age 39 years for women and 49 years for men.

Overall, the incidence of T1D is increasing by 2% to 3% per year, especially in non-Caucasian ethnicities that are more typically associated with being at higher risk for developing T2D:

Prevalence of T1D

The prevalence of people with T1D in the US was 1.9 million people in 2019 (the proportion of the population living with T1D, regardless of when initially diagnosed). Of those, only 13% were children or adolescents. This may be due to the newer insulin treatments and the benefits of technology. Many young people are living with T1D well into older ages. The harsh reality is that those diagnosed with T1D between ages 11 and 15 years will experience a shorter lifespan by an estimated 12 years compared with their counterparts who do not have T1D.

As with any chronic disease, the earlier it is detected and treatment is initiated, the better the odds the person will do well and for a longer duration. There are approximately 300,000 people currently at risk for overt T1D.

Who is Most at Risk?

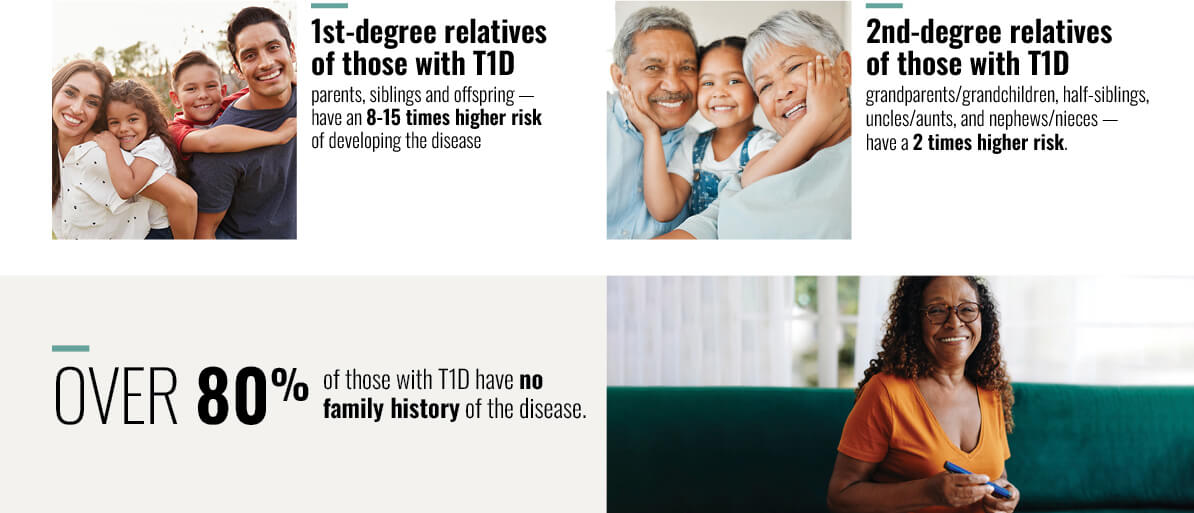

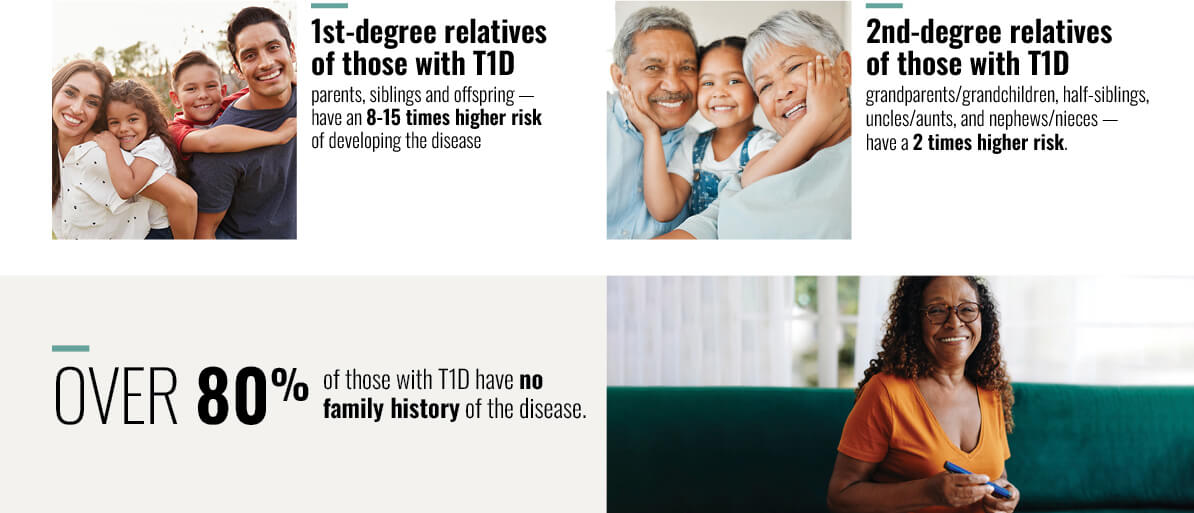

It is understood that autoimmune disorders generally coexist in individuals and tend to cluster in families. Meaning, people with one autoimmune disorder are more likely to have another disorder, and those with a family history of autoimmune disorders have a higher risk of developing an autoimmune disorder.

People who have a first-degree family member (parent or sibling) with T1D are 8 to 15 times more likely than the general population to develop it. If we include second-degree relatives with T1D (grandparents, aunts/uncles, nieces/nephews), the risk is 2-fold greater. However, nearly 80% of people with a new-onset T1D will not have a family history.

Additionally, people with other autoimmune disorders also have a higher prevalence of having T1D. Therefore, DCESs and HCPs must be aware of other autoimmune disorders associated with T1D and include this knowledge in the risk assessment of determining whom to screen.

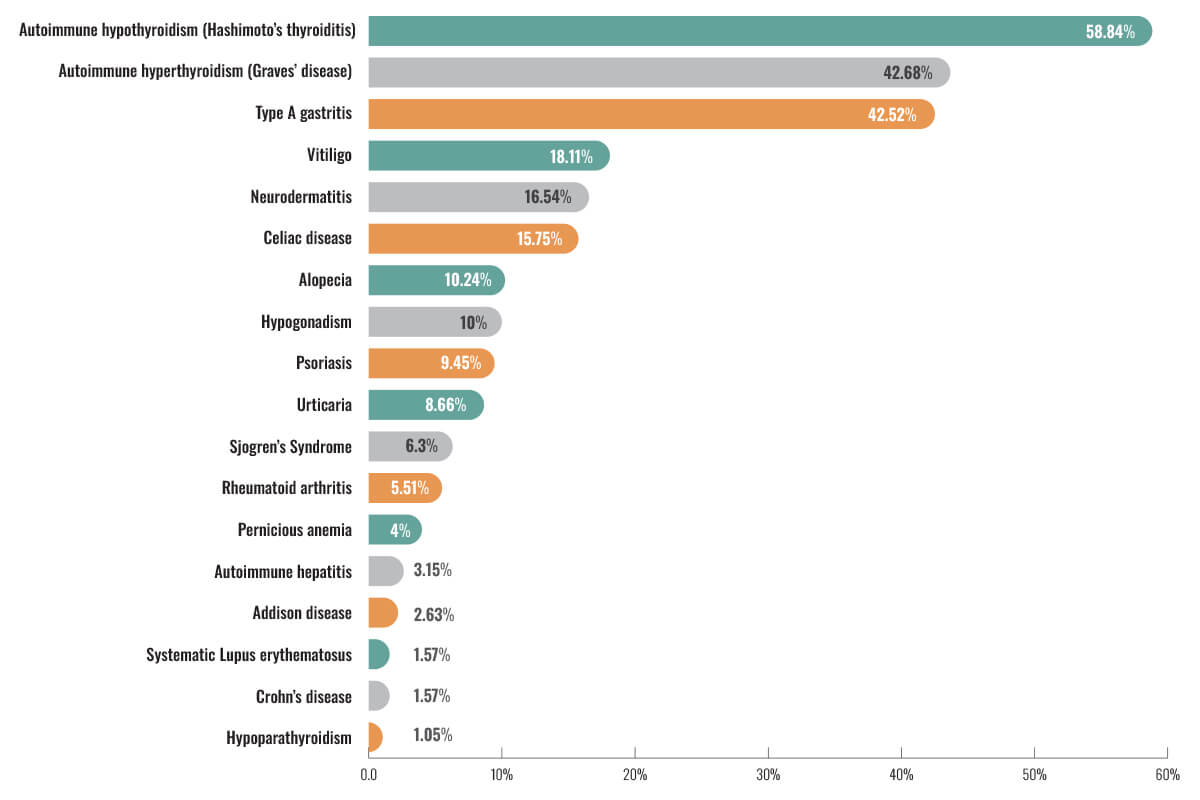

The Autoimmune Disorder Connection

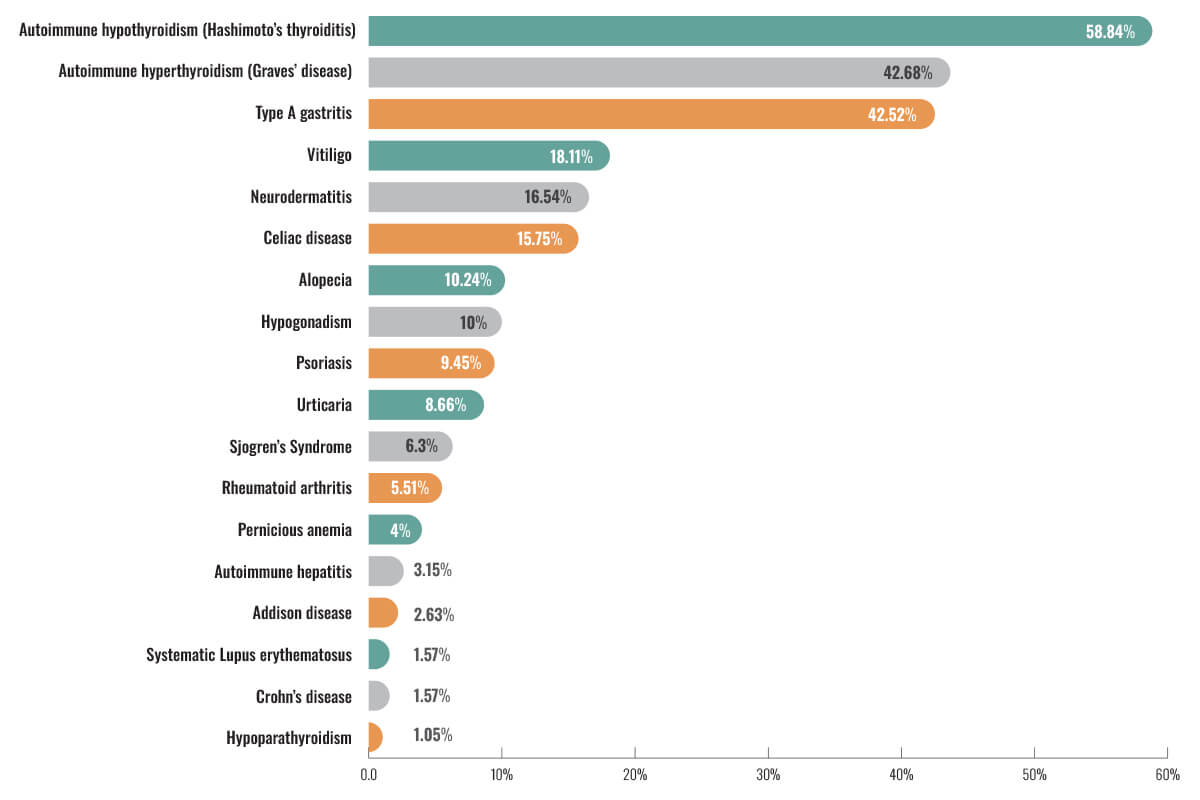

The ADA’s Standards of Care in Diabetes recommends all people diagnosed with T1D be specifically screened for autoimmune hypothyroidism soon after diagnosis. This is because 17% to 30% of people with T1D will have autoimmune thyroid disorders compared with just 1.5% to 10% of people without T1D. This is similar to celiac disease where about 8% of those with T1D will have celiac disease compared to just 1% of the general population. Screening for celiac disease is encouraged when there are signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders/distress. Pernicious anemia is another autoimmune disorder common in people with T1D. Because vitamin B12 deficiency can cause neuropathy, which is already common in people with DM, serum B12 levels should be assessed with symptoms of neuropathy and/or findings of macrocytic anemia. An observational study published in the World Journal of Diabetes in 2020 identified the prevalence of autoimmune disorders in people with T1D.

The results are as follows:

Unfortunately, the reverse association between the risk of other autoimmune

disorders and the future development of T1D is not as clear. However, this

study did identify that compared to people who had T1D without other autoimmune

disorders, those with T1D and at least one other autoimmune disorder (most

often autoimmune hypothyroidism) were more often female and older. Autoimmune thyroid

disorders tend to occur in women between age 40 and 60 years. The onset of T1D

in people with autoimmune thyroid tends to develop later and after the onset of

autoimmune thyroid disorders.

The strong association between these autoimmune disorders with T1D warrants a

high degree of suspicion. When screening individuals for T2D (starting at age

35 years in all adults) yields abnormal

glucose and/or A1C values, they have a personal or family history of any of the

above autoimmune disorders, and they lack signs, symptoms, and disorders

typically associated with insulin resistance and T2D (eg, dyslipidemia,

hypertension), screening for T1D would be indicated.

Traditional Diagnosis for T1D

The ADA has long published recommendations

regarding who to screen, when, and how often based on defined risk factors for

T2D. In the absence of risk factors, we have guidance as to when to screen

based solely on age. To the contrary, until recently, the screening

recommendations as well as the appropriate testing for T1D have not been clear.

It was not until 2017 that the main autoimmune antibody tests were made

commercially available. However, the tests have not been widely implemented

into clinical practice since then.

The

lack of screening is at least one reason that 28% to 40% of children diagnosed

with T1D will present with the life-threatening hyperglycemic crisis known as

diabetes-related ketoacidosis (DKA). It is the leading cause of mortality in

youth with T1D. The frustration is knowing that these events are potentially avoidable

or at least less likely to occur if T1D is identified in the pre-clinical

stages.

In many cases, especially in families with no prior history of T1D, early

symptoms of DKA are unrecognized or misunderstood. Therefore, seeking medical

treatment is delayed and may not be administered until the person is critically

ill. Diabetes-related ketoacidosis occurs less frequently

among children or siblings of people with T1D or those who are aware of the

symptoms. Why? They know what to look for and how to act quickly.

Health care professionals are aware of the 3 Ps (i.e., polyuria, polydipsia,

polyphagia) and unexplained weight loss as classic symptoms of hyperglycemia.

We must translate this into simple language that nonclinical people can

understand. For example, Diabetes UK launched a national campaign known as the

4T’s (i.e., toilet, thirsty, tired, thinner). Heightening awareness of these

symptoms may ensure the person receives potentially life-saving treatment much sooner

and possibly avoid the risk of developing DKA altogether.

Breakthroughs in T1D Screening

The glucose and A1C parameters for diagnosing diabetes are the same for T1D

and T2D. However, these measures alone do not classify the type of diabetes nor

are they the most effective ways to screen for T1D. By the time someone with preclinical

T1D (stage 1 – positive for 2 or more autoantibodies but normal glucose) develops

abnormally elevated glucose in the range of pre-diabetes (stage 2), they

typically rapidly progress to overt T1D (stage 3, hyperglycemia). This is

especially evident in children and adolescents.

In addition, T1D has historically been viewed as a childhood or adolescent

disease, and that has led to many adults being misdiagnosed as having T2D. Of

the new cases of T1D diagnosed each year, 58% occur in adults compared to

children and adolescents. Therefore, if an adult with diabetes is classified as

having T2D and 1) has a personal or family history of other autoimmune associated

with T1D; or 2) is not responding well to appropriate treatment for T2D,

they should be screened for delayed-onset T1D, known as LADA.

The ADA's Screening Recommendations: Our New Call to Action!

The ADA recommends screening for the presence of the following autoantibodies in individuals with a family history of T1D, as well as those with a personal or family history of other autoimmune disorders: insulin autoantibodies, antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase, antibodies to the zinc transporter, antibodies to the tyrosine phosphatase-related islet antigen 2.

The positive findings of at least 2 autoantibodies and glucose and A1C consistent with prediabetes (stage 2) yield a 44% likelihood of the individual progressing to overt T1D (stage 3) within 5 years; a 70% likelihood within 10 years; an 84% likelihood within 15 years, and an overall lifetime risk of 100%.

The value of identifying T1D antibodies: Time ‒ the Most Valuable Commodity

Accurately identifying a person's risk for developing T1D before any

symptoms are experienced can empower individuals to become educated about the

disease process and how to recognize symptoms of hyperglycemia to reduce the

risk for DKA. Knowing they are at risk

will encourage HCPs to refer their patients to DCESs and other health professionals for education that includes the

latest available treatment options.

When referred to a DCES, there is an opportunity to provide education and resources

pertaining to self-management of diabetes before it develops! We can

all provide information about health precautions and guidance that will help to

alleviate the associated shock and anxiety of this diagnosis and can spend time

to ensure individuals and families start their journey well-equipped and

supported to live their best lives.

Key Takeaways

- Autoimmune disorders including T1D are on the rise globally affecting ethnicities not traditionally associated with T1D.

- Adults make up 58% of those newly diagnosed with T1D each year.

- Screening and identifying those at risk for T1D can significantly reduce the risk for DKA – a life-threatening, acute complication of hyperglycemia.

Guidance on clinical assessment, adjustments, report interpretation and key education. Designed to be used during clinic visits.

Guidance on clinical assessment, adjustments, report interpretation and key education. Designed to be used during clinic visits.-(3).jpg?sfvrsn=16486d59_5)

-(1).png?sfvrsn=799e9a59_1)